BIG BLUE FANS FOR

BASKETBALL

2015-16 Season Analytical Writings

32A

Upsets! Upsets! Upsets!

Coaches, Pundits, Fans, and Casual observers of the game talk almost endlessly about upsets in college basketball. How many occur? Are upsets on the rise?

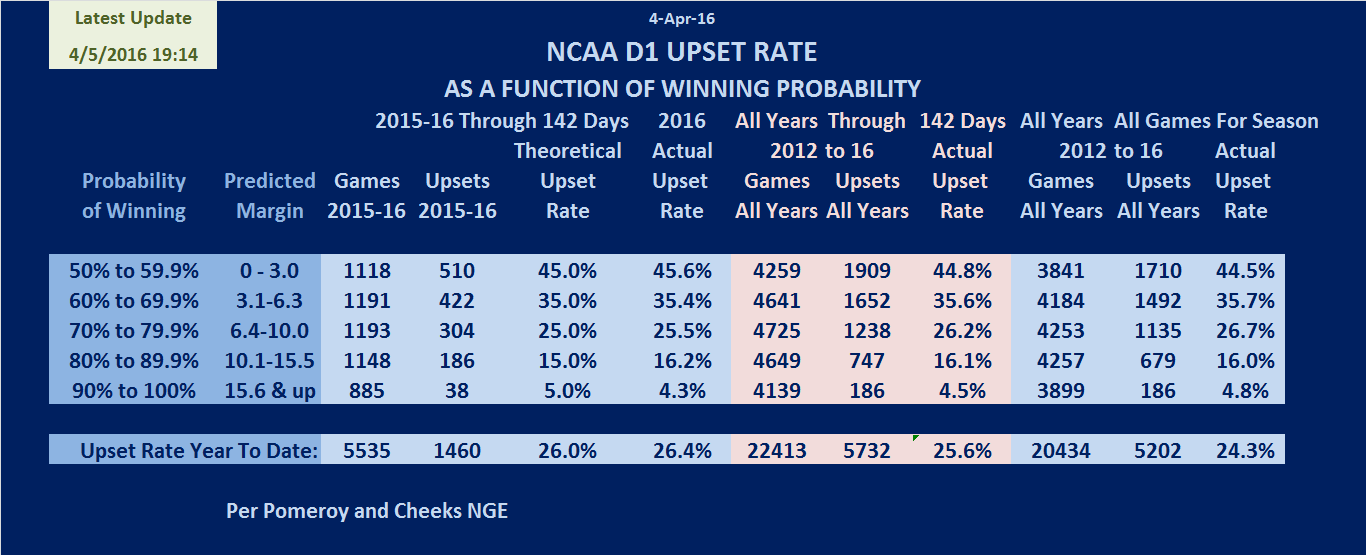

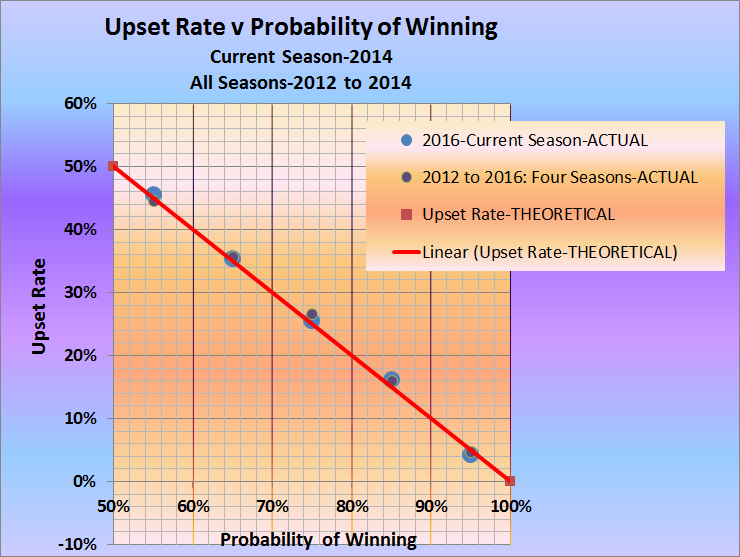

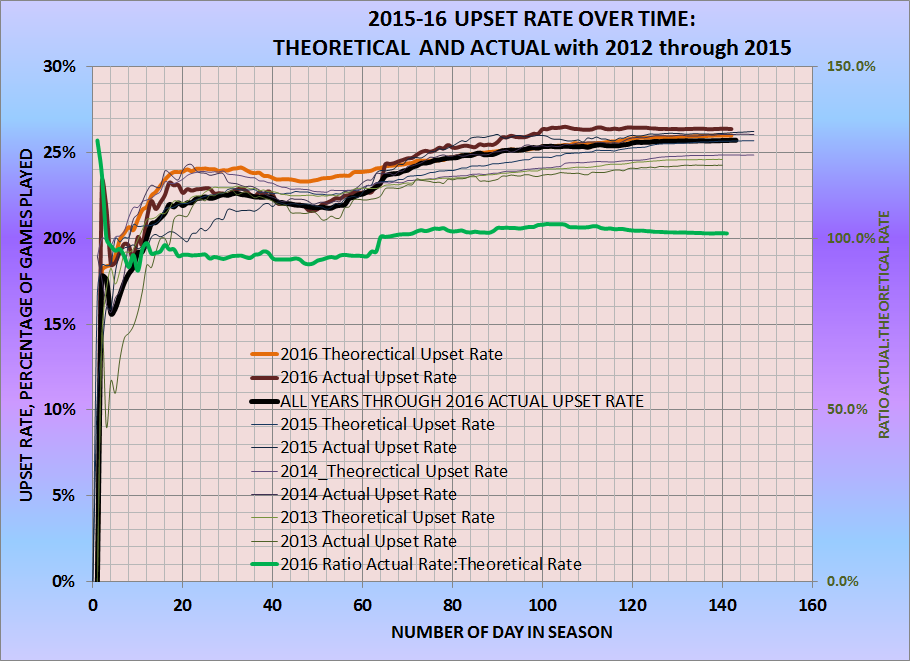

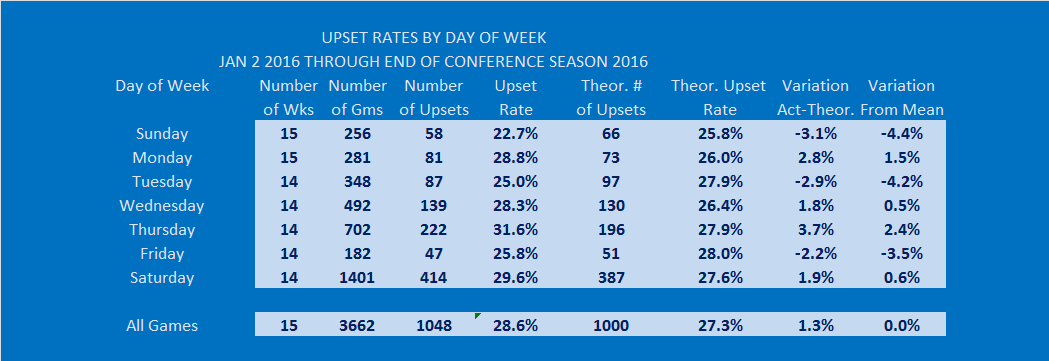

Over the last several seasons, I have tracked upsets in college basketball. In a thumbnail, about 1 in 4 college basketball games ends with the favored team losing to the underdog. This is true year after year. However, there are some subtleties in the data. Second, the source of this data is Pomeroy's pregame probabilities and the actual outcomes, and the favored team is the team with the higher pregame probability of winning, even if the probability is approaching 50%. When the probability of winning is in the 50 to 59.9% range, over the years the favorite team has won 55.5% of the games. At the other end of the spectrum, when the probability of winning is in the 90-99.9% range, the favorite team has won 95.2% of the games. Similar relationships exist for the other 10 percent ranges.

The data bases for this analysis consists of over 20,000 basketball games, spanning the last 5 seasons. The year ending upset rate in these five seasons has ranged from a low of 24.2% to a high of 26.1%.

Every fan seems to pin their hopes (and dreams) about their team's standing and likelihood of future success on some aspect of the upset. Fans of the top teams bemoan the simple occurrence of upsets as interfering with their team's ability to be even better than their record may seem. Fans of the bottom teams are eternally encouraged by the occurrence of upsets as indicative of how good their struggling team really can be. However, for the vast majority of fans who follow teams that are not the upper crust or the bottom dregs, they cite the occurrence of upsets as why their teams need to be more consistent.

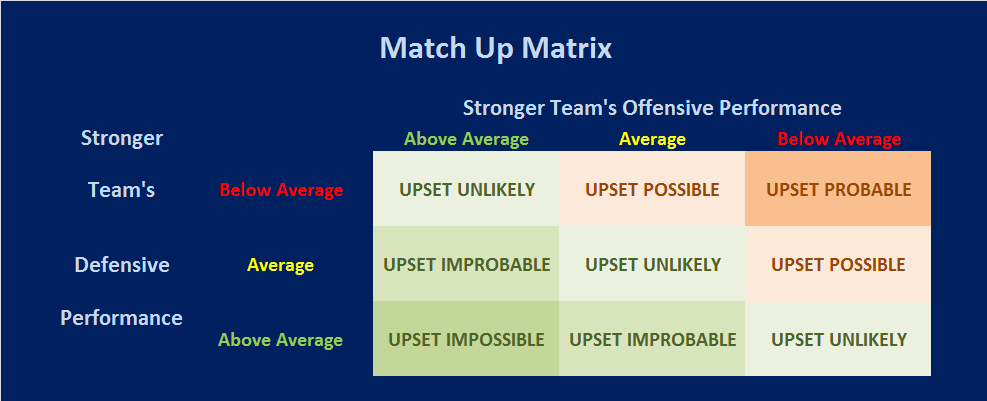

No team is perfectly consistent. This is a human activity, and performance will vary. The average performance is a significant measure, but inherent in any average measure is the reality that about 1/2 of all performances have been better than that average and about 1/2 of all performances have been below that average. Teams at the top rarely play teams that have "better" average performance levels, so when upsets occur for teams at or near the top, the upset is almost always a loss to an inferior team. Similarly, for teams at the bottom, their upsets are almost always a win over a superior team. However, for the vast majority of teams, those that neither reside near the top or the bottom, their upsets are split between wins over teams that are better and losses to teams that are weaken.

One rule of thumb for most teams is a team will experience about 8 upset games over the course of a 32 game season (25%), and four of those will be upset wins and four of those would be upset losses. As teams move toward either the top or bottom of the pile, the number of anticipated upsets declines, and the ratio of upset wins to upset losses shifts as noted previously.

Is there a better day of the week to play games when it comes to upsets? It appears that there could be. When teams play on Sunday, Tuesday, or Friday, the actual number of upsets is less than the theoretical number of upsets. However, for games on Monday, Wednesday, and Thursday the number of upsets exceeds the theoretical number. Of these upset prone days, the most vulnerable days are Thursday and Monday.

On Saturday (when the largest sample size of games exists) the variation between actual and theoretical upsets is very close to 0.

Submitted by Richard Cheeks

Submitted by Richard Cheeks

![]()

To Cats Go To Vandy In Search Of Upset Win

Go Back

Cats Rebound For Big Win Over Alabama

Copyright 2016

SugarHill Communications of Kentucky

All Rights Reserved